Children, Pain, and Rorschach Images

This article, in a slightly edited form, first appeared on Pain News Network on October 5, 2019.

How a Child Responds to Pain

No one saw it happen. My three-and-a-half-year-old granddaughter was in the basement by herself when she broke her arm. My guess is that she was jumping on the couch or standing on the back of it. Either way, the accident left her screaming and crying—a natural response to being frightened and/or injured. At the time, it wasn’t clear if she was seriously hurt, but according to her mother, she behaved very differently from how she had acted when previous falls had resulted in bumps and bruises.

In a previous blog, “Teaching Children to Cope With Pain,” I wrote about how parents should respond to children when they injure themselves. Experiencing pain is part of life, and children develop their own reactions based on an almost infinite number of factors.

As adults, we tend to think about the physical trauma pain causes. We pay scant attention to how the young brain processes injuries, or the images created in their minds as a result of the injury.

Children’s brains are unable to process trauma in the way adults do. This is, in part, due to the limited verbal ability children have to express what they are feeling. Still, they do integrate the experience of pain. Hopefully, the lessons they learn about their ability to manage their pain during their childhood help them cope with pain when they reach adulthood.

Images of Pain

Working with images, or drawing, is one way to help children effectively process their pain. The symbolic meaning of an image can be very revealing. Sigmund Freud described how the imagery we’re attracted to can reflect feelings, attitudes, and qualities of our environment.

Hermann Rorschach famously built on that idea to develop the Rorschach (or inkblot) test. The concept (in this context) of the Rorschach test is that through drawing or interpreting images, children can convey the emotional loads they carry.

The first collection of children’s drawings of pain was published in 1885, well before Rorschach developed his test. It appeared in an article written by art reformer Ebenezer Cookie and illustrated how the stages of children’s development corresponded to the clarity of their drawings.

All trauma has the potential to affect a child’s development and perspective. This does not mean that all trauma damages the brain or renders a child unable to manage stress. In fact, trauma is a life experience that children must learn to manage without compromising their emotional development. That sets the stage for being able to handle pain effectively as they mature.

In his book, Hardwiring Happiness: The New Brain Science of Contentment, Calm, and Confidence, neuropsychologist Rick Hanson says, “Your brain was wired in such a way when it evolved, it was primed to learn quickly from bad experiences but not so much from the good ones.” That explains why traumatic memories so often stick in our brains while positive memories seem to slip away. “It’s an ancient survival mechanism that turned the brain into Velcro for the negative, but Teflon for the positive,” Hanson concludes.

On the day of my granddaughter’s injury, my daughter told me about the incident and asked for my help. Fortunately, my wife and I live nearby, so I rushed over immediately. Even before I entered her home, I began to wonder whether the injury my granddaughter experienced would be more Teflon than Velcro.

Usually, when I arrive, my granddaughter calls my name and races to give me a hug. That didn’t happen on the day she fell. Instead, she was clinging to her mother, who was trying, and failing, to console her and “make it all better.”

It was obvious to me that my granddaughter had a fracture and needed to be taken to the emergency room.

After the orthopedic surgeon had reduced and cast her arm, my granddaughter experienced minimal pain. It was a bump in the road she would one day forget. Or would she? And should she?

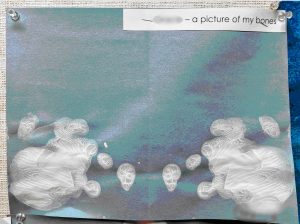

Two weeks later, my granddaughter was at preschool, where the class was studying cloud formations. Each student was asked to draw clouds and explain what their Rorschach images meant to them.

Above, you can see my granddaughter’s drawing (which she made by applying blobs of ink to the paper and folding it in half). Her interpretation of that image was that the clouds were “my broken bones.”

Teflon or Velcro?

The separation of the clouds might have been the projection Freud would have expected from a child with a recent injury where bones were separated and had to be reduced.

It reinforced the lesson for me that young children are always processing and interpreting the events of their lives. These experiences create images and memories that are a part of their developing brains and personalities.

Although my granddaughter is only three and a half, she is already forming her adult interpretation of pain, one layer at a time. Whether her experience will be more Teflon than Velcro, only time will tell.

Lynn R. Webster, MD, is a vice president of scientific affairs for PRA Health Sciences and consults with the pharmaceutical industry. He is author of the award-winning book, “The Painful Truth,” and co-producer of the documentary, “It Hurts Until You Die.”

You can find him on Twitter: @LynnRWebsterMD.

Opinions expressed here are those of the author alone and do not reflect the views or policy of PRA Health Sciences.